The Ministry of Information last week banned South African company DSTV (owned by Multichoice, itself owned by South African media giant Naspers) from broadcasting Premier League football in Nigeria. The Ministry’s decision was based on the fact that DSTV had been granted continent-wide exclusive rights, which stifles local competition and contravenes Nigerian broadcasting law. The ban has therefore been imposed in order to break this monopoly and support local media players.

This decision should be celebrated, on one level at least, simply on the principle that governments anywhere in the world should try as hard as they can within their powers to encourage local media ownership and break up external monopolies (if only this were practised in the UK against Murdoch!) DSTV beams in South-Africa centric images into the homes of those that can afford it in Nigeria (even the odd advert is in Afrikaans - usually for some tacky sub-Val Doonican singer), which can only be construed as a form of insidious cultural imperialism, however subtle.

However, to Nigerian futebol fans (there are millions), this decision by fiat has denied them access to their favourite league, perhaps for the rest of the season. It is doubtful whether there is any serious local competition with sufficient current capacity to offer anything like the meagre choice offered up in DSTV’s bouquet (how many people who signed up are happy with Trumpet or FSTV’s rival output?) The government should have sorted these issues out well in advance of the start of the season. Imagine that an ownership-rights war erupted in the middle of the Premier League season in the UK, with no resolution in sight? Well, that’s exactly what is happening here.

As one commentator has pointed out, DSTV/Multichoice have only themselves to blame for the decision - access to the footie is one of the major reasons why people who can afford it fork out N9000 per month at present (around 35 UK pounds). Theirs has been a rent-seeking mentality, collecting cash for access to international content, with no clear interest in developing local content in Nigeria. They have no programme of sponsorship (such as local sports), no local studios and therefore no apparent interest in developing local culture. This was a strategic error, which is now returning to haunt them. For instance, we probably wouldn’t be at this point now if DSTV had made a major investment in promoting the Nigerian Football league..

Even if the decision to stop DSTV’s exclusive broadcasting rights to the Premier League was politically motivated, or the result of favoured lobbying to Information Minister Frank Nweke (which some are saying), and even though the decision is a case of bad timing from a fan’s perspective, the decision is I think one to be supported. However, there is much to be done in supporting the development of local media players interested in transmitting both local and international content – both for satellite/cable bouquet broadcasters and TV stations. The broadcast quality of local players is appalling (they are using antique broadcasting equipment in outdated studios with inferior production facilities), and the content is amateur. Serious local funding from the banks (who after all, are desperate to find good investment opportunities with their broadened shareholder base) is required to enable global-standard media services to emerge. The vision should be for Nigeria to enable an African competitor to CNN to appear: an Al-Jazeera for the continent.

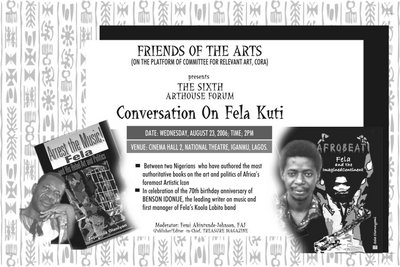

At the same time, the question of whether a modern democratic nation-state should actually have a ‘Ministry of Information’ needs to be questioned (doesn’t this hark back to colonial times and the need for a state-controlled propaganda vehicle?), as the question also needs to be asked whether this ministry should have direct ownership of the largest local TV station, NTA. A transformation into a ‘Ministry of Culture’ function promoting local cultural events, the arts etc with increasing autonomy given to NTA, along the lines of the BBC, should surely be the more deeper programme of change. And as part of this, why not have an Arts Council of Nigeria structured alongside the Arts Council of Britain – supporting professionalisation in film, theatre, literature, dance etc? Perhaps the break-up of DSTV’s monopoly is the first stage of this change agenda. One would hope so.

The one hundred dollar computer – a good idea?

Meanwhile, the Nigerian government has agreed to buy one million of MIT Professor Negroponte’s one hundred dollar laptops. At the same time, the Indian government, which initially had allotted the same amount for its poorest students, has cancelled their order. One might ask why the Indians took the decision and Nigeria has not. Surely, the root of the issue is whether owning a laptop will actually help poor Nigerian students (and poor Nigerian workers). Well, it will enable them to learn to type, learn word-processing and spreadsheet packages, which are the essential basic skills of any student wishing to offer themselves to the national (if not international) job market. However, ownership of a cheap laptop does not provide anyone with access to information, surely a more fundamental requirement of a globalising world.

If only the Nigerian government would commit similar funds to building a national IT backbone for the country, including a gateway to the outside world via an alternative to the cartel-strangulated subterranean cable SAT-3. The consequence of this plan (cheap access to cross-country broadband) would arguably have a much more transformative effect on Nigeria’s citizenry than any amount of laptops shipped in to the country. The other downside of course is that bringing in so many laptops has the unintended side effect of depressing the local box-production market. No wonder Zinox et al are up in arms. The good news is that it does look like the IT backbone issue is being addressed, however, there is still no sign that a SAT-3 competitor is in sight (Globacom remains the only glint of light on the horizon).

One can’t help wondering whether the government continues to fear the liberalisation of information flows (witness the refusal in the past two administrations to sign a community-radio bill). Again, one can’t help wondering whether the stale argument of ‘defending African culture and values’ against international information flows (as witnessed in the DSTV decision and in countless press tirades against Channel O and MTV Base videos) is in part motivated by an elite power structure that all too readily is able to anticipate the erosion of its base should increasingly globalised flows of information be allowed to be pumped into the country. In this respect, a "China syndrome" haunts the government, which can only act as an impediment to increasing development and democratisation.

Until a Nigerian administration fully embraces globalisation (both in terms of informational inputs and outputs), the people will continue to be misinformed and locked within limited codes of understanding. Propagandist regimes need to learn the paradoxical and difficult lesson that letting go (of media control) can actually lead to increased empowerment, at least from the perspective of strengthening democratic processes. As Blair's infatuation with Murdoch has shown (he is rumoured to be taking a place on the Murdoch board when he steps down), this is not a lesson learnt easily in the West, let alone elsewhere.

This surely reflects a subconscious lack of confidence; it implies that globalised informational inputs will dilute or pervert local culture. Given the historical influence of various Nigerian cultures (perhaps most notably, Yoruba culture) on international cultural movements, it is doubtful whether this would in fact happen. Rather, it is more likely that globalised inputs would be quickly Nigerianised, and then reflectively expressed back to the world. One only fully appreciates the context which enabled one's identity when one travels outside. This principle writ large and when applied to increasing global inputs into Nigerian society, would probably engender a more reflective and expressively articulated set of cultural outputs.

But of course, it would mean that the government would have to give up its role as arbiter of cultural values, enabling a more distributed model of cultural re-interpretation to take place. At some point, this fear-factor has to be engaged and challenged, for young Nigerians to claim their place within a global culture.

Read more...

Medieval city of staircases and prince-bishops, ghosts of tapestries past, and post-industrial anomie. A city with many names: Liege (French), Luttich (German), Liuk (Flemish/Dutch). The city breathes out smoke, and sucks in history. Sizeable Arab and Italian populations give the city a cosmopolitan air, but nowhere is there glamour. I fall in love with the jazz on its streets (especially in the Carré), late into the night watching musicians enter, kiss each other and unzip saxophones, while I sip biere Trappiste with new friends I only half understand. An Italian guy with fat fingers bangs out standards on an electric piano with effortless grace, while a guy I will know later as Mimi plays guitar with such fluidity I lose my breath. Miles was here just before he died (last year).

Medieval city of staircases and prince-bishops, ghosts of tapestries past, and post-industrial anomie. A city with many names: Liege (French), Luttich (German), Liuk (Flemish/Dutch). The city breathes out smoke, and sucks in history. Sizeable Arab and Italian populations give the city a cosmopolitan air, but nowhere is there glamour. I fall in love with the jazz on its streets (especially in the Carré), late into the night watching musicians enter, kiss each other and unzip saxophones, while I sip biere Trappiste with new friends I only half understand. An Italian guy with fat fingers bangs out standards on an electric piano with effortless grace, while a guy I will know later as Mimi plays guitar with such fluidity I lose my breath. Miles was here just before he died (last year).